-

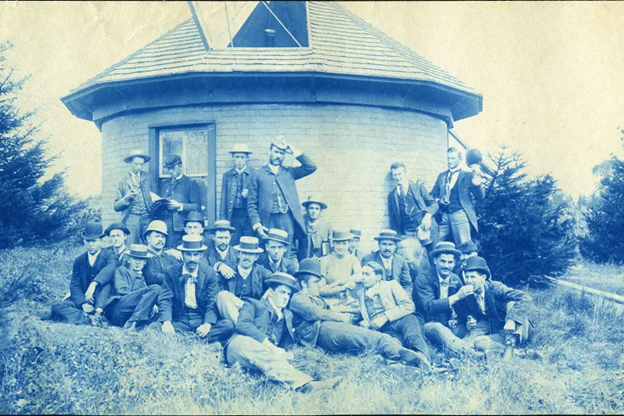

Campus Archaeology Program Uncovers Foundations of MSU’s First Observatory

Discovery gives insight into campus history, provides educational opportunities In summer of 2023, workers from Michigan State University Infrastructure Planning and Facilities, or IPF, were installing hammock posts close to student residence halls near West Circle Drive when they encountered a hard, impenetrable surface under the ground. Believing it to be either a large rock […]

-

MSU Biomarker Laboratory for Anthropological Research is seeking mid-Michigan breastfeeding mothers for upcoming study

Department of Anthropology Associate Professor Masako Fujita, Director of the MSU Biomarker Laboratory for Anthropological Research, is looking for mid-Michigan breastfeeding mothers to volunteer for an upcoming study, “Exploring Human Milk Immune Specificity.” Qualifying volunteers will be asked to:

-

Associate Professor Heather Howard named the recipient of the 2023 College of Social Science Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Excellence Award

Associate Professor of Anthropology Dr. Heather Howard has been named the College of Social Science’s recipient of the Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) Award. This award recognizes a faculty member who plays a leadership role in advancing diversity, equity, and inclusion by demonstrating activities which may include serving underrepresented populations, developing or implementing innovative programs […]

-

Society of Antiquaries elects first MSU professor Dr. Ethan Watrall as fellow

The Society of Antiquaries elected Dr. Ethan Watrall, associate professor in the Michigan State University Department of Anthropology, as a fellow. The Society of Antiquaries was founded in 1707, and represents the oldest learned and prominent scholarly society focusing on heritage and archaeology. The society’s 3,000 elected members include some of the most prominent scholars and […]

-

Anthropology undergraduate Levi Webb: Passion for the stars and the people below them

Levi Webb’s academic advisor suggested he add a minor in computational modeling or mathematics, a more “typical” pathway for an astrophysics major, but after taking anthropology-based ISS courses on different cultures and perspectives, Webb decided to follow his passion. “As someone who earned an International Baccalaureate Diploma in high school and, thus, came to MSU […]

-

Campus Archaeology Fieldschool’s Excavation of MSU’s First Observatory Featured in Local Media

In summer of 2023, workers from Michigan State University Infrastructure Planning and Facilities, were installing hammock posts close to student residence halls near West Circle Drive when they encountered a hard, impenetrable surface under the ground. The discovery turned out to be the archaeological remains of MSU’s first observatory. Located just behind what is now Wills […]

-

The Department of Anthropology Welcomes new MSU Museum Archaeology Collections Manager, Samantha Ellens

The Department of Anthropology is happy to welcome the new MSU Museum Archaeology Collections Manager, Samantha Ellens. The position of Collections Manager is jointly supported by the MSU Museum and the Department of Anthropology. Samantha will be responsible for the care, preservation, and documentation of the archaeological collections that are managed and curated collaboratively by […]

-

Associate Professor Dr. Masako Fujita publishes in American Journal of Human Biology

Department of Anthropology Associate Professor Dr. Masako Fujita, along with her student Amulya Vankayalapati of Lyman Briggs College at Michigan State University and her veterinary epidemiologist collaborator George Wamwere-Njoroge of the International Livestock Research Institute in Kenya, has published an article in American Journal of Human Biology. The article is titled “Effects of household composition […]

-

Professor Dr. Gabriel Wrobel receives Fulbright Specialist Award to Belize at Institute of Archaeology

Department of Anthropology Professor Dr. Gabriel Wrobel has been awarded the Fulbright Specialist Award to complete a project with the Institute of Archaeology in Belize. At the Belize Institute of Archaeology, Dr. Wrobel will be giving talks about archaeology, cultural heritage, bioarchaeology, and digital heritage for high school and college students with the goal of […]

-

Associate Professor Dr. Mara Leichtman publishes in Ethnography

Department of Anthropology Associate Professor Dr. Mara Leichtman published an article in Ethnography, in part of a special journal issue titled “Transnational Giving: Evolving Religious, Ethnic and Political Formations in the Global South.” The article title is “Humanitarian Sovereignty, Exceptional Muslims, and the Transnational Making of Kuwaiti Citizens.” This article explores the changing relationship between […]